A critical examination of the production of meaning in the contemporary English language cycling media

Note: This is a recreation of the 2007-published Cycles of Representation, based on unfinished files on floppy disks (remember those?). It differs from the published version you may have read, and from the version available in archives.

CHAPTER TWO: STRUCTURES OF INFLUENCE – THE VALUES INHERENT IN CYCLING MEDIA TEXTS

The structures, influences and systems through which the English language cycling media produces consumable texts are intrinsically linked to the construction of meaning through systems of representation based around the construction of identities, allusion to existing perceptions, and the constant reappearance and reassertion of cycling’s historical grandeur. This equation of meaning through the mediation of particular values positions cycling as a specific site through which audiences consume not only a sequence of events or a narrativised version of a sequence of events, but also a series of ideas, principles and expectations.

These representations largely serve the purpose, as with other sports, of positing professional road cycle racing in a way that will appeal to its audience and perpetuate the sport. Whilst the motivation behind these representations is essentially capitalist, this does not necessarily apply to the representations themselves, whose underlying goal is to both construct and recycle existing understandings and beliefs in a way that can create the strongest narratives or sense of engagement with events. This chapter will examine three of the main ways through which these existing understandings and beliefs are reconstructed and recycled by the cycling media, and situate the extent to which the cycling media’s role is less about reporting events than it is constructing meanings for those events.

“English-speaking riders” and transnational identities

One of the ways in which meaning is constructed in the English language cycling media is through the means by which “English-speaking riders” are used and represented. The term itself is ambiguous – it does not refer simply to riders who can speak the English language, but instead to riders from particular Anglophone, Anglo-Saxon countries. The inference is that several countries (namely Great Britain, America, Australia, and South Africa) separated by thousands of miles have a common relationship that cannot exist with the “foreign” other of mainland Europe.

The motives behind this inference are not necessarily profit-driven – whilst markets for a homogenised global cycling coverage certainly exist, the resistance of using this term to refer to riders from other profitable Anglophone markets such as Canada and Eire suggests instead the reproduction of an Anglo-Saxon cultural identity of superiority from which the “weaker” colonies and “Celtic underdogs” are to be excluded. (Dauncey & Hare, 2003:17-18).

This transnational identity is able to exist through the models of postmodernisation and commodification of the production of cycling media texts outlined in the previous chapter:

The lesson from media sport is that whereas the rhetoric of national identity is about uncomplicated allegiance to a nation based, singly or variously, on place of residence, place of birth or parental lineage, support for a nation is in fact surprisingly provisional, and easily transferable. The indications are that the ongoing commodification and globalisation of sport is influencing the cultural and social significance of national identities.

Brookes, 2002:84

Thus, the concept of national identity within sports is ephemeral, a dynamically produced constant process based around the cultural and social significances of a particular epoch. (ibid. 89). Indeed, rather than a simple cultural construction, nation can be understood as an imagined community built upon a series of “rituals, daily practices, techniques, institutions, manners and customs which enable the nation to be thinkable, inhabitable, communicable and therefore governable” (Mercer, 1992:27, cited in Brookes, 2002:86). But the malleability of national identity and its position as ritualistic community process does not necessarily imply that the role of nationalism in maintaining identities is under threat. Citing Meyrowitz, Brookes dismisses the idea that “Postmodernists argue that new communications technologies will replace place-defined collective identities with ‘communities of interest’ that have ‘no sense of place’” (Brookes, 2002:84), arguing instead that the “economics of media sport” reproduce national differences, rather than undermine them (ibid. 85).

Brookes’s dismissal of the postmodernist technological approach to understanding the relationship between communications technologies and national identities might initially seem to contradict the evidence presented so far in this essay, but to some extent this is correct. The transnational identity of the “English-speaking riders” might be a “community of interest” to an extent, but it is certainly grounded in real-world physical location. The English language cycling media’s adoption of Anglo-Saxon riders can be seen in the same way as English rugby fans are expected to support Great Britain in international tournaments, and golf fans to support Europe in the Ryder Cup. National identities in the sports media are thus “the site of competing discourses” (Brookes, 2002:106), and can shift to best represent particular values.

These constructions of transnational identity within cycle sport are thus not so much an economic decision, but rather an extension of the tendency of fans to use sports as a commodity to define the self (Ashworth, 1970:40-41). Britain’s tendency to cling to its Imperial past means that its political framework and postcolonial identity is such that the difference between its representation of sport and the ways in which sporting events are represented in continental Europe

can be explained in terms of the degree of political modernity, so that in Britain/England sporting success or failure comes to stand in for the success or failure of the nation in general, in the rest of Europe sporting success or failure is only one way of being and does not come to stand in for the nation as a whole.

Brookes, 94-95

By placing extra emphasis on the worth of victory to national identity and relating it to external social values, coverage of road cycling – in which Anglo-Saxon culture is very much in the minority – demands a broader definition of national identity to provide both the results and audience support required to maintain its existence. As a result, “English-speaking riders”, an amalgam of Anglo-Saxon culture, occupy the mediated position of representing this culture in a cordon of foreign otherness.

As such, the referral to “English-speaking riders” provides a foundation from which to develop allegiances within the competing discourses of national identity (Brookes, 2002:106), offering a racialised, culturalised standpoint for the audience to take in the consumption of constructed narratives. The audience is informed which stars embody and epitomise aspects of the (trans-)national character (Whannel, 2002:166), and are thus positioned in a situation whereby they can consume the media text within a preferred reading.

The “other media”

One of the ways that this construction of an Anglo-Saxon ideology is reinforced is through the allocation of “otherness”. Unlike the findings of studies into particular sports, this otherness was rarely projected onto the participants themselves, whose existence was necessary for the construction of heroism that shaped cycling’s representation, and who continue to provide avenues for the construction of narratives. Instead, this otherness was given to two parties: the fans, and the media.

Non-Anglo-Saxon cycling fans were not characterised inherently negatively, yet their otherness remained evident in their representation through constructions of stereotypes and generalisations that did not correspond to the lack of visibility of fans from Anglophone countries. Foreign fans were thus orientalised in their representations – from the suave Italian fans depicted at the Giro d’Italia, to their zealous, passionate compatriots in the tifosi, to the French fans obsessed with national character, to the Flemings whose fondness of watching cycling, eating frites and drinking lager is so strong that it leads to them standing in adverse weather conditions. Their otherness is exemplified through the shallow, generalised communities of identity that represent them in comparison to the solid, innate bond that represents Anglo-Saxon fans.

However, it is the media itself that is often the most constructed “other”. Reports of important cycling news from French and Spanish newspapers – whose position as the media in countries where cycling is not a niche sport can allow them to investigate much more comprehensively than their Anglo-Saxon counterparts – are often discussed within the English language cycling media, but afforded very little credibility. L’Equipe’s 2005 front-page article “The Armstrong Lie” was met with incredulity by the English language cycling media and, as a telling indication of how the media’s representations can shape perceptions, was also dismissed by most Anglo-Saxon cycling fans, the majority of whom lacked access to the text itself. Detractors argued that L’Equipe was in the business of selling newspapers, a claim that was certainly truthful although far from a solid basis for argument – L’Equipe being in the business of selling newspapers is no more evidence as to their lying as Armstrong being in the business of winning Tours de France would be evidence of his cheating. Further criticisms levelled at L’Equipe were to the credibility of their argument, describing the article as the result of a French vendetta against America, and accusing the newspaper of trying to force the Union Cycliste International and World Anti-Doping Agency into taking action against Armstrong on the basis of the article. The extent to which the article has credibility is difficult to gauge, especially given that the case in question was not officially investigated to a significant degree, but the inference of lack of journalistic ethics and the extent to which the issue became racialised, nationalised and politicised in the English language media should not be ignored. Nor should the fact that many of the criticisms that were made with the intention of disparaging L’Equipe’s reporting are alluded to in the very article itself:

However, these latter conclusions could be hasty, as the American has never tested positive since anti-doping controls of the 2000 Tour. And, paradoxically enough, this affair should have no disciplinary consequences. The retrospective analyses … have in fact been done with the use of the B-samples from the 1999 samples, which were all negative … and very few sample residues were left … Furthermore, the B-samples were only used for experimental analysis and the procedures followed don’t correspond with requirements set by the anti-doping procedures … There won’t be any counterexpertise, nor any statutory consequences, as the defendant’s rights can’t be respected.”

L’Equipe, August 23, 2005

The non-Anglophone press is thus prescribed the traditional values of otherness, the same values that are so often inflicted upon various social others, be they based on gender, class or race – the media is portrayed as untrustworthy, irrationally guided by its own subjective opinions and willing to break traditional rule structures. That the criticisms levelled at the non-Anglophone cycling media are largely invalid or immeasurable is secondary to the connotations constructed by the projection of deviance upon a generalised, foreign “institution” of “otherness”.

This “otherness” is not simply reserved for the non-English language media, however. The Times newspaper was dismissed in the cycling press for its decision to publish extracts of the book L.A. Confidentiel. (The Times, June 2004). The media maintained the pressure against The Times, an aspect of the media outside to the sport, when Lance Armstrong, the subject of the extract in question, sued the newspaper for libel. This ostracisation of the outside media is a long standing tradition of the cycling media (Maso, 2005), and the new Anglo-Saxon media cliques have appropriated this in their contemporary practice.

Likewise, the American Floyd Landis, who was briefly the winner of the 2006 Tour de France before testing positive for exogenous testosterone, mounted a large-scale PR campaign within the three pillars of the cycling media protesting his innocence and complaining of being the victim of a “trial by media”. That his campaign used the very media he was complaining about was of little consequence, instead there was posited a dangerous, amoral media of which he was a victim. This other media was not a physical entity, and nor did it need to be – it was enough to suggest an objectified otherness, an enemy within from which he and other Anglo-Saxon riders were under threat.

Traditional values: Cycling’s heritage

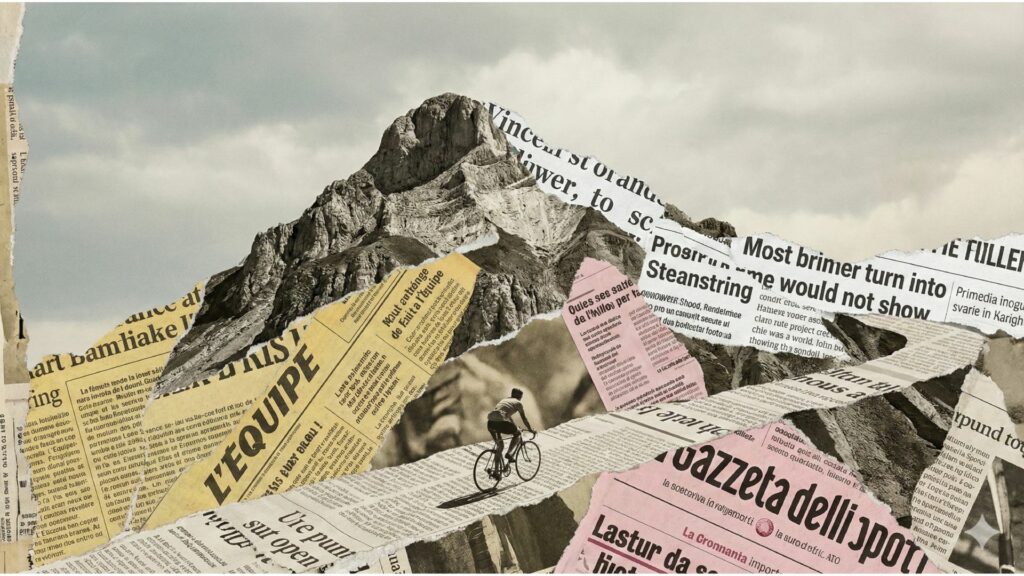

Despite the postmodern shifts described in the previous chapter, the English language cycling media does largely promote cycling’s proud heritage and long-standing traditions and values. The worth of a heritage of mythical riders, inspiring, exciting races and the incredible strain of the hardest sport on earth is not a difficult one to place – it is typical and vital for mediasport to utilise its symbiosis to reassert its value to fans.

The grandeur of cycling is constantly asserted through the English language media. Magazines regularly feature “retro” features, discussing events from races that have usually taken place more than twenty years prior to publishing. Furthermore, it is habitual to refer to particular events with allusion to other, previous events – Floyd Landis’s stage win in the 2006 Tour de France was compared with the “greats” of cycling history, notably Koblet and Coppi of 1951 and 1949/1952 respectively; the Operacion Puerto drugs case of 2006 was related to the ‘Festina Affair’ of 1998; the Giro d’Italia’s crossing of the Colle delle Finestre in 2005 was represented with sepia-toned television coverage to further assert its relationship to cycling’s “golden days.”

These references provide constant reminders as to the current value of the sport. By relating particular current events to an illustrious, romanticised past, a sense of ‘making history’ is constructed – simply, audiences will engage more with the sport if there is a perceived potential to see the development of the next of these ‘classic rides’. The English language media’s fascination with presenting contemporary cycling as a constantly developing sport making its own position in historical representations is further alluded to by Eurosport’s television coverage, whose presenters are prompted to explicitly refer to viewers who are “watching cycling for the first time.” Whilst it is true that such viewers might exist for the Tour de France, it is unlikely that the numbers of non-cycling audiences tuning into Eurosport in anticipation of the ENECO Tour of Benelux would be so significant as to warrant the dedication of airtime to explain the rules of the sport. Instead, this reference implies that there are, indeed, rapidly growing numbers of new audiences for cycle sport, and furthermore allows aficionados of the sport a position in which their knowledge of cycling culture is something that maps them out from other fans. As well as maintaining audience interest, the idea that particular fans have arrived too late to witness the events that other cycling fans have throughout their time spent following the sport adds further value to these events that can now only be experienced retrospectively, and therefore incompletely. Essentially, by appealing to memory, the process invents – or perhaps imposes – tradition through a symbolic dimension.

This is not a new phenomenon. Cycle sport has used the media to invent its own tradition since the beginning of the twentieth century. The first Tour de France in 1903 used a route that mapped out a very particular geography of France, designed to instil memory and nostalgia. (Dauncey & Hare, 2003:8). Through the mediation of this race, a series of rules and conventions were devised, constructing a culture for the Tour and inventing its tradition (ibid). The extent to which tradition is constructed can be seen in the example of the Tour’s “first” mountain, the Ballon d’Alsace. In fact, the Tour’s director, Henri Desgrange, included the mountain in an attempt to find new ways to make the Tour continue to be considered the hardest race for its competitors. That the 1903 and 1904 Tours de France climbed the Col de la République, only seventeen metres lower than the Ballon did not stop L’Auto from presenting this move as unprecedented and dangerous. (Maso, 2005:21-22). Not only is this mountain recorded as the first in virtually all histories of the Tour, but the 2004 Tour de France route also paid its own homage by crossing it. The heritage constructed by Henri Desgrange in 1905 to increase the public’s perception of the brutality of the Tour remains evident in the media today.

The contemporary English language cycling media continues to support the construction of heritage. Like the media of old, it reinforces the tradition of events and situations that would otherwise be considered new. However, it also affords particular values to sites of Anglo-Saxon successes – the Col de Madone, for example, is referred to in the same breath as the “legendary” mountains in cycle sport largely because Lance Armstrong annually used it to train his climbing ability ready for the Tour de France.

By constructing a heritage for cycle sport, the ephemeral nature of mediasport becomes more “real”, and presents a history and culture that can be used as a background for the creation, dissemination and legitimisation of mediated representations and meanings.

Conclusion

The English language cycling media translates the system of production discussed in the previous chapter into a highly structured, self-perpetuating system built around the construction of narrativised discourses of representation and implicit signifiers of particular meanings.

Through the construction of an Anglo-Saxon identity, the media is able to embody and situate an audience’s preferred reading through a system of pre-existing values and connotations. It is telling that “the fundamental generative principles of ‘French’ sporting characteristics are to be discovered in the interactions between French and ‘Anglo-Saxon’ culture.” (Dauncey & Hare, 2003:17). Cycling media from non-Anglophone nations too, it would appear, use nationalistic and cultural “difference” as a tool from which to define identity.

This difference is also a tool through which other connotations can be made. Cycling fans from non-Anglophone nations are presented with a jovial representation as a wild and outrageous other; the foreign media less so. So too do other aspects of cycling use otherness as a defining tool, such as the example of Floyd Landis attempting to gain public support by playing off public concerns about a renegade, unethical media capable of diminishing reputations, presenting a dangerous other as a simple threat from which to recover.

The importance of “heritage” to cycling is one of the most significant ways in which meaning is attached to particular events. The cycling media’s fascination with representations of the past and the positioning of the present in relation to it is not necessarily unique, but certainly contrasts with more ubiquitous sports such as football, in which the emphasis is placed largely on the future, which teams will win which competitions. The cycling media recognise the worth of a strongly represented tradition, a system “imposed from above” that consists of a “set of practices dedicated to inculcating and exemplifying values of historical unity that stress continuity and solidarity despite profound social change.” (Rowe, McKay & Miller, 1998:123).

Ultimately, by focusing on these key spheres of influence rather than attempting a comprehensive survey of production methods, we can better understand how the cycling media prepares its texts for audience consumption.

Footnotes

1 – A report of then-recent procedural retrospective laboratory tests on the American seven-times Tour de France winner Lance Armstrong’s urine samples from the 1999 Tour de France that indicated the use of the white-blood cell boosting agent, erythropoietin